Date: 01/01/2000The dot-com bubble (also known as the dot-com boom, the tech bubble, the Internet bubble, the dot-com collapse, and the information technology bubble) was a historic speculative bubble covering roughly 1995–2001 during which stock markets in industrialized nations saw their equity value rise rapidly from growth in the Internet sector and related fields. While the latter part was a boom and bust cycle, the Internet boom is sometimes meant to refer to the steady commercial growth of the Internet with the advent of the World Wide Web, as exemplified by the first release of the Mosaic web browser in 1993, and continuing through the 1990s.

A year ago Americans could hardly run an errand without picking up a stock tip. Day-trading manuals were selling briskly. Neighbors were speaking a foreign tongue, carrying on about B2B’s and praising the likes of JDS Uniphase and Qualcomm. Venture capital firms were throwing money at any and all dot-coms to help them build market share, never mind whether they could ever be profitable. It was a brave new era, in which more than a dozen fledgling dot-coms that nobody had ever heard of could pay $2 million of other people’s money for a Super Bowl commercial.

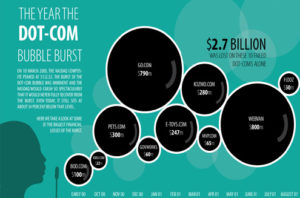

What a difference a year makes. The Nasdaq sank. Stock tips have been replaced with talk of recession. Many pioneering dot-coms are out of business or barely surviving. The Dow Jones Internet Index, made up of dot-com blue chips, is down more than 72 percent since March. Online retailers Priceline and eToys, former Wall Street darlings, have seen their stock prices fall more than 99 percent from their highs.

Unlike the worrisome decline in the stock prices of solidly grounded technology firms due to a slowdown in profits, the sharper plunge taken by some of the trendy Internet companies that had no earnings in the first place has proved comforting to those who believe in the rationality of markets. After all, many of them lacked one key asset — a sensible business plan. Even the most traditional brokers and investment banks set aside the notion that a company’s stock price should reflect its profits and urged investors not to miss out on the gold rush. At the craze’s zenith, Priceline, the money-losing online ticket seller, was worth more than the airlines that provided its inventory.

The current sense of despair in the dot-com universe may be as overdone as last year’s euphoria. The Internet, after all, really is a transforming technology that has revolutionized the way we communicate. What recent months suggest, however, is that it may not be an indiscriminate, magical new means of making money.

Woeful tales of visionary innovators failing to capitalize on their revolutionary new technology are not new. The advent of railroads, the automobile and radio, to name other watershed innovations in history, also led to many a shattered dream. The number of failed auto makers far exceeded the number that ultimately succeeded.

In this holiday season, the financial implosion of so many dot-com retailers seems particularly cruel. It is not as if consumers do not appreciate shopping online. Online sales this season are expected to be about two-thirds greater than last year. But it is not the innovators who are reaping all the benefits. Online retailers are losing market share to the likes of Wal-Mart and Kmart. This holiday season, online sales of traditional retailers, initially hesitant to embrace the Web, will outpace those of the pure dot-coms for the first time.

The endearing Pets.com sock puppet is a fitting mascot for the demise of the dot-com mania. Less than a year ago the spokesdog for the online pet-supply retailer was starring in some of those $2 million Super Bowl commercials. Now, in the wake of his master’s bankruptcy, he is looking to shill for another company — one that can actually make money.

Factors That Led to the Dot-Com Bubble Burst

There were two primary factors that led to the burst of the Internet bubble:

The Use of Metrics That Ignored Cash Flow. Many analysts focused on aspects of individual businesses that had nothing to do with how they generated revenue or their cash flow. For example, one theory is that the Internet bubble burst due to a preoccupation with the “network theory,” which stated the value of a network increased exponentially as the series of nodes (computers hosting the network) increased. Although this concept made sense, it neglected one of the most important aspects of valuing the network: the ability of the company to use the network to generate cash and produce profits for investors.

Significantly Overvalued Stocks. In addition to focusing on unnecessary metrics, analysts used very high multipliers in their models and formulas for valuing Internet companies, which resulted in unrealistic and overly optimistic values. Although more conservative analysts disagreed, their recommendations were virtually drowned out by the overwhelming hype in the financial community around Internet stocks.

Avoiding Another Internet Bubble

Considering that the last Internet bubble cost investors trillions, getting caught in another is among the last things an investor would want to do. In order to make better investment decisions (and avoid repeating history), there are important considerations to keep in mind.

- Popularity Does Not Equal Profit

Sites such as Facebook and Twitter have received a ton of attention, but that does not mean they are worth investing in. Rather than focusing on which companies have the most buzz, it is better to investigate whether a company follows solid business fundamentals.

Although hot Internet stocks will often do well in the short-term, they may not be reliable as long-term investments. In the long run, stocks usually need a strong revenue source to perform well as investments.

- Many Companies Are Too Speculative

Companies are appraised by measuring their future profitability. However, speculative investments can be dangerous, as valuations are sometimes overly optimistic. This may be the case for Facebook. Given that Facebook may be making less than $1 billion a year in profits, it is hard to justify valuing the company at $100 billion.

Never invest in a company based solely on the hopes of what might happen unless it’s backed by real numbers. Instead, make sure you have strong data to support that analysis – or, at least, some reasonable expectation for improvement.

- Sound Business Models Are Essential

In contrast to Facebook, Twitter does not have a profitable business model, or any true method to make money. Many investors were not realistic concerning revenue growth during the first Internet bubble, and this is a mistake that should not be repeated. Never invest in a company that lacks a sound business model, much less a company that hasn’t even figured out how to generate revenue.

- Basic Business Fundamentals Cannot Be Ignored

When determining whether to invest in a specific company, there are several solid financial variables that must be examined, such as the company’s overall debt, profit margin, dividend payouts, and sales forecasts. In other words, it takes a lot more than a good idea for a company to be successful. For example, MySpace was a very popular social networking site that ended up losing over $1 billion between 2004 and 2010.