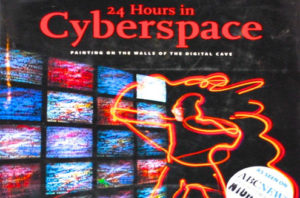

Date: 01/01/199624 Hours in Cyberspace (February 8, 1996) was “the largest one-day online event” up to that date, headed by photographer Rick Smolan with Jennifer Erwitt, Tom Melcher, Samir Arora and Clement Mok. The project brought together the world’s top 1,000 photographers, editors, programmers, and interactive designers to create a digital time capsule of online life.”

Overview

24 Hours in Cyberspace was an online project which took place on the then-active website, cyber24.com (and is still online at a mirror website maintained by Georgia Tech). At the time, it was billed as the “largest collaborative Internet event ever”, involving thousands of photographers from all over the world, including 150 of the world’s top photojournalists. Then Second Lady Tipper Gore was one of its photographers. In addition, then Vice President Al Gore contributed the introductory essay to the Earthwatch section of the website. In this essay, he discusses the impact of the Internet on the environment, education, and increased communication between people. The goal was not to show pictures of websites and computer monitors, but rather images of people whose lives were affected by the use of the growing Internet. Photographs were sent digitally to editors working real-time to choose the best pictures to put on the project’s website. The website received more than 4 million hits in the 24 hours that the project was active.

24 Hours in Cyberspace served as a cover story for U.S. News and World Report.

The technological infrastructure of the project was provided by a startup company spinoff from Apple Computer named NetObjects that was founded by Samir Arora, David Kleinberg, Clement Mok and Sal Arora. The system supplied by NetObjects allowed Smolan’s international network of editors and photojounalists to submit text and images through web forms; it ran on Unix, relied on a database for content storage (Illustra) and used templating for easy and near-instantaneous page generation that obviated the need for the site’s editorial staff to have any coding skills. NetObjects was first to create the technology that would enable a team of the world’s top picture editors and writers to become instant Web page designers. It let them do what they do best—edit and write—and automatically generate finished, sophisticated Web pages that millions of people were able to see only minutes after they were designed. Three million people clicked onto the 24 Hours site; the blaze of publicity surrounding the 24 Hours in Cyberspace project helped NetObjects raise $5.4 million in venture capital.

The project reportedly cost as much as $5 million, and was funded with assistance from 50 companies, mostly in the form of loans of computer hardware and technology experts. Adobe Systems, Sun Microsystems and Kodak were listed as major supporters. 1996: “Cyberspace” is not yet a household word but is about to get a big boost in the public consciousness with an international, one-day event, 24 Hours in Cyberspace. Top editors, photographers, computer programmers and designers, contributing from all over the world, collaborated to document a single day on the internet. It became not only a digital time capsule but a coming-out party, of sorts, for a medium whose impact was as dramatic in its day as television was a half century earlier. 24 Hours in Cyberspace was the inspiration of photographer Rick Smolan, who created the “Day in the Life” photo-essay series. Smolan used the same formula as “Day in the Life,” recruiting 150 photojournalists to go out and chronicle a slice of everyday life, in this case as it pertained to the then-counterculturish phenomenon of the web. The technology of the internet was not the subject: Smolan wanted (and got) pictures of how different people in different cultures were using the internet, and the effect that the medium of cyberspace was having on their lives.

The resulting work was edited and then displayed on a website. It also appeared as the cover story of that week’s edition of U.S. News and World Report and, soon thereafter, as a coffee-table book. The project, billed as the “largest one-day online event,” cost around $5 million and was bankrolled by companies — like Sun Microsystems and Adobe — with a vested interest in the internet’s growth, as well as by individual contributors.

As it turned out, Feb. 8, 1996, fell on the very day that President Bill Clinton signed the Communications Decency Act (later overturned in court). Many activists turned their websites black that day, a protest mentioned briefly on the 24 Hours website and in the book.